Last year’s Housecore Horror Film Festival was a celebration of an unusual talent in the history of cinema. Alan Ormsby is the definitive underground hero, a filmmaking polymath (writer, director, actor, make-up effects artist) who is beloved of hardened horror fans, but still

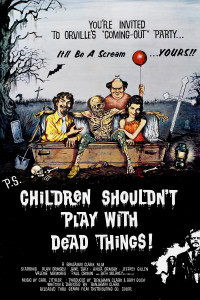

Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things (recently released on Blu-ray by VCI Entertainment) was the first in a series of Ormsby’s collaborations with Bob Clark. Two years later, Clark produced the Ed Gein-inspiredDeranged for writer/co-director Ormsby, before directing Ormsby’s script for post-Vietnam horror Deathdream. After their partnership collapsed, Ormsby went on to have a career in Hollywood, plus he designed the massively popular Hugo: Man of a Thousand Faces dress-up doll.

However, it’s his first film that is probably his most famous. Appearing in between the revolutionary Night of the Living Dead and the equally epoch-changing The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, it was a quirky outlier – satirical, gory (for the era).

(A shorter version of this interview appeared in the Austin Chronicle)

Richard Whittaker: You’ve been the star attraction and celebrated filmmaker at this festival. Looking back, how does it feel going back and looking at this run of your career?

Alan Ormsby: Children seems to have been around a lot. It was in drive-ins and than it was on TV for years, whereas the other two had really disappeared. I was surprised a couple of years ago to see that they had a following. They put them out on DVD and I did a commentary on Death Dream and Children and Deranged. I was amazed. Obviously, it’s had some influence, along with The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

RW: In Austin, the Alamo Drafthouse has a regular night called Terror Tuesday, where they find 70s and 80s films on 35mm, and I know that Death Dream and Deranged have turned up on more than a few occasions. But Death Dream is a very heavily anti-war movie, particularly in the context of Vietnam. So what was the genesis of that, knowing that you’re going to piss some people off?

AO: You have to project yourself back into the late 60s and early 70s. The anti-war feeling was huge. It was really a divisive thing on every side. It wasn’t right wing versus left necessarily – I mean, it was in some places. I wanted to do an anti-war horror movie, and there really wasn’t one. Maybe going back to the 40s, there was one about Dreyfus, but hardly ever was there anything like that, so it was more original than we thought at the time. The script got some serious attention in New York at the time, but I have to say that I think that the fact that it became more of a genre piece worked against it in some funny way. they wouldn’t take it seriously as an anti-war film, but it wasn’t quite drive-in fodder. It is at the end, but it sort of got lost. But it did get some recognition. It got an award at the Sitges film festival, and here or there somebody would write an article or mention it, but it was disappointing. Also, they couldn’t quite find the right title, and they kept changing the title.

RW: The version they showed here was Dead of Night …

AO: … which of course was a famous British anthology film. But it’s nice to see that people appreciate it now. I mean, you can’t do anything about the technology. It’s a lot cruder back then than it is now. There was no Internet, no video, all this very sophisticated blood making. It looks so real, so utterly real. I think Deranged looks pretty good. It has this dirty, dingy, despairing feel to it that was probably just the location we used.

RW: People had danced around Ed Gein, but part of Deranged‘s position in horror is that it dives at him head-on. Tobe (Hooper) filtered the influence, and so did Hitchcock in Psycho. Aside from some ‘redacted for legal reasons’ stuff, you were much closer. So how did you develop the script?

AO: It was not developed. Basically, Tom Carr said ‘I want to make a movie about Ed Gein,’ and he gave me these articles, and I just wrote the script, and he put in his two cents, and then (co-writer Jeff Gillen) and I set about making a shooting script out of it. We probably made a few little changes – not many though – and I basically took it out of the newspaper clippings. I just wanted him to be this innocent psycopath. In a way, Norman Bates is a little like that, isn’t he. Of course, that’s the great movie made out of Ed Gein, Psycho. We didn’t have time to do develop. There was no development. You wrote it, and if it was too expensive, you cut it. That was it.

Children was really a slap-dash script, patched together. I realize watching it that Val, who died on November 6, I think she wrote her scene where she went into her Yentl, Jewish momma thing. I didn’t write, and I’m sure Bob didn’t write it, so I’m sure that she wrote her own scene. The actors threw in lines.

RW: The famous conjuration, I could see that being a writer’s dream because you can go as purple as you like. It’s a torrent of alliteration.

AO: I think I wrote that, and I know I wrote a lot of the stuff at the end in the cabin. It’s kind of like Bob said, ‘I don’t have time to write this, can you write this and can you add scenes here and there?’ It’s really hard to remember. I have the script still at home, but it’s still hard to tell what I did. It was a blend of everybody really. But it was very purple. Matter of fact, I didn’t like the script when I first read it. It was too much talk and not enough action. Now I like it as just what it is, but I kinda wish we had gone the Texas Chain Saw route, it’s expensive and time-consuming to shoot action, and we just didn’t have the money or the time. We put all the money in the zombies.

RW: It seems like it was one of the definitive run-and-gun productions. You were everywhere: you were writing, you were performing. How physically tough was it to just get it done in such a short time?

AO: I was young, so that helped. I was watching it, and I realized that my shirt was soaking wet, all the time. Writing it, and then building all these make-up pieces, and then putting the make-up on, and then acting it. I did the advertising even, and I promoted it at various conventions. It was fun, I had a good time. We didn’t make any money, it was $200 a week, if that, but when you’re young and you just want to make a movie, you don’t think about anything else. There was no sense of TV rights, sequel rights, video. I wish there had been, because I guess the trade-off is when you’re young, and you do one of these low-budget movies, you’re not going to make any money on it, but they’re going to make money on it, and they’re going to make money for the next 40 years, and 40 years later you’re sitting there watching it on television, feeling pissed off because there’s your work, and you’re not getting anything, but somebody is. That was one of the fallings-out I had with Bob Clarke, was over money, of course.

RW: Much like Chain Saw, where money is still a sore point to this day.

AO: That particular movie captures something specific, without a lot of gore. People think it’s really gory, but it’s not.

RW: They couldn’t afford it.

AO: Well, you don’t need it.

RW: One of the most memorable moments in Children is when Allan throws Anya to the zombies, and the zombies look at him like, we’re going to eat her, but you’re a terrible human being.

AO: Bob must have had it in for me, because he made me the worst character. I have no redeeming features at all.

RW: Children is the first time you worked with Bob Clarke. How did you meet?

AO: We knew each other in school, in college. We did plays together and so forth. We both wrote plays and we both acted in each other’s plays, and about five years after that, I was back in Miami and I ran into him on the street, and he said, “I’ve got some money to make a horror movie, have you got any ideas?” I told him that I wanted to see Night of the Living Dead, which was playing at some theater. So we went to see that, and that’s where all of this came from. We just ripped it off, and added a lot of dialogue.

RW: One thing everyone notices is that you play a character called Alan.

AO: [Bob] wanted to use our real names, except for Jane, the ingenue, because he said it would make it easier for him to recognize us in the edit. He wanted to do a Cassavetes thing.

RW: Bob was director, but you did some of everything else. You co-wrote, acted, did the special effects.

AO: I did the make-up in my mother’s kitchen.

RW: How much did your theatre background prepare you for cinema?

AO: I wanted to be an actor – not after this – and I wanted to be a make-up man. I wanted to do monster make-up. When this came along, I thought, well, I think I can do it, because I’ve done masks. Then I did the make-up, and I just decided I didn’t want to do make-up. It just wasn’t my alternate thing.

RW: Night of the Living Dead is clearly over your shoulder, but this was still really early in the history of zombie films. How much did you expect that people would know the rules, and how much did you have to explain what zombies are?

AO: I think that, because people had seen Night of the Living Dead, they took it for granted that zombies ate you. So I don’t think we gave it much thought. It’s not like today, when there’s The Walking Dead and 50,000 other zombie movies. Everybody knows the rules at this point, but we just assumed they did.

The movie doesn’t make sense to me, because I keep thinking, where did I get this power over people? They’re members of a theatre troupe in Miami, and I’m threatening them with losing their jobs. If you’ve ever done theatre in Miami, you know it’s not a money-making enterprise. So every time I say it, I wonder, why do they listen to me? I’m such an asshole, and they just take it.

I also realized tonight that Val is the one that raises the dead, not me. Never got that before.

RW: We have to clarify: where did you find those pants?

AO: There’s a story attached to that. The zombie with the big bulging eyes and the suit, I had to make a head cast of him, and I forgot to do the ears. So when I had to take the cast off, his ears were stuck. So I had to call the producer and say, I think Bruce is going to loose his ears, because I can’t get the plaster off of him. This poor guy, it was horrible. So then he became the costume guy, and I’m totally convinced that was his revenge.