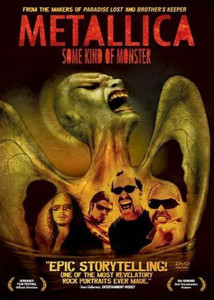

There aren’t many celebrity documentarians, but Joe Berlinger is probably on that short list. He established a reputation as director of the groundbreaking crime investigations Brother’s Keeper and Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills and became globally known for his warts-and-warts-and-more-warts-‘n’-all rockumentary, Metallica: Some Kind of Monster. But his follow-up documentary, Crude, drops him into the middle of geopolitics, following the complicated battle over pollution in the Amazon fought between the massed corporate power of the U.S.-based Chevron oil company and the lawyers representing the Ecuadorian tribes whose ancient lifestyle and homelands face devastation. Berlinger describes it as a return to his filmmaking roots, with a minimal crew and almost no external financing. Traveling from Chevron’s corporate headquarters to remote villages in what he called “an area of border disputes and drug runners,” he charts the seemingly endless court case and the ecological genocide that devastates the region.

There aren’t many celebrity documentarians, but Joe Berlinger is probably on that short list. He established a reputation as director of the groundbreaking crime investigations Brother’s Keeper and Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills and became globally known for his warts-and-warts-and-more-warts-‘n’-all rockumentary, Metallica: Some Kind of Monster. But his follow-up documentary, Crude, drops him into the middle of geopolitics, following the complicated battle over pollution in the Amazon fought between the massed corporate power of the U.S.-based Chevron oil company and the lawyers representing the Ecuadorian tribes whose ancient lifestyle and homelands face devastation. Berlinger describes it as a return to his filmmaking roots, with a minimal crew and almost no external financing. Traveling from Chevron’s corporate headquarters to remote villages in what he called “an area of border disputes and drug runners,” he charts the seemingly endless court case and the ecological genocide that devastates the region.

Richard Whittaker: For such a huge international story, it seems like almost nobody has heard about the trial. How did you find out about it?

Joe Berlinger: One of the things that attracted me to the story is that it was being swept under the rug here. Any national, corporately owned media tends to shy away from any story that might offend big advertisers. And I never imagined that this would become my next big film, but I thought a spotlight should be shone on the situation once I saw it. Basically, what happened was that [U.S. attorney] Steven Donziger – we have a mutual friend who told me about this case. Donziger came to my office, and I said right off the bat: “I may not be the kind of filmmaker you may want to cover the story. I’m known for a more observational style, where I allow both sides to tell their point of view, and it sounds like you want more kind of an agitprop piece. The truth rises to the top.” He said, “That sounds good to me.”

RW: So when did you realize that this was a story deserving of a full feature?

JB: On the second day that we were there, we were meeting [Ecuadorian attorney Pablo Fajardo Mendoza] at this indigenous Cofán village. When I was getting out of the boat, I saw five or six villagers sitting around the campfire, eating canned tuna – the cheapest industrial can of tuna from whatever the Ecuadorian equivalent of Costco or Sam’s Club would be, because the river next to them wasn’t producing fish anymore because of all the pollution. That image stuck with me, and this was before meeting Pablo and before he took this incredible journey from oil-field worker to lead attorney on the case.

RW: After basically being recruited by the plaintiffs, was it hard to convince Chevron to go on the record?

JB: It took me a year and a half. I had originally wanted them to come down and take me on a toxitour – that’s what the plaintiffs call it when they take people on a tour of the oil pits. I pleaded with them, “Take me on a toxitour from your perspective; let me sit in on some of your meetings.” It took a long time to win their trust, and finally, I said:”This film is locking; this is my deadline. I’m aiming to submit this to Sundance; this is now your last deadline.” With a little help from a guy at Hill & Knowlton, which is one of their publicity firms, I told them the absolute truth: “that I’m sure they’d rather a film not be made, but a film is being made, and you might as well have your side of the story in it.” After an in-person lunch and lots of phone calls, they agreed to the interviews. It was literally at the last minute, which played well into the film, because two weeks after, [Chevron attorney] Ricardo Reis Veiga was indicted for fraud by the Ecuadorian government. I don’t think they would have agreed had that indictment come down earlier.

RW: You started making Crude before the Chevron pollution case became an international scandal, and Some Kind of Monster before Metallica nearly imploded. Right place, right time?

RW: You started making Crude before the Chevron pollution case became an international scandal, and Some Kind of Monster before Metallica nearly imploded. Right place, right time?

JB: There’s been a huge string of luck in my career. That’s definitely something that’s hard for me to explain. The first time I was sitting filming a therapy session for Metallica, that was right after my complete and utter failure on Blair Witch 2, where I got eviscerated by the press, I think a little too hard. I certainly took it hard.

AC: How tough was that?

JB: It wasn’t that the movie was reviewed badly, it was that I was reviewed badly. I was gutted, personally, over this movie. It was hard to take. So I myself needed therapy, and I was sitting in this room watching James Hetfield starting the process of baring his soul, thinking to myself, ‘I don’t know why I’m here or how I got here, but even if this film goes nowhere, I”m also hitting 40. I’m also having a great professional and existential crisis, just like these guys. So I really need to hear this shit.’ I just find myself in those situations. Is it all luck? I like to think of the old cliched definition of luck as opportunity meeting preparation.

RW: So how much preparation was it? Seems like the band was very comfortable with you.

JB: The reason we met Metallica is because, in Paradise Lost, Metallica lyrics are introduced into the trial, and we felt like we had to have their music in the movie, even though they have a reputation for never allowing that up to that point. They were hard to get a hold of, and a lot of people wouldn’t have expected us to successfully navigate that. We ended up getting the music for free, we developed a friendship. When Jason (Newstead) quit the band and the therapist arrived on the scene, I’m not sure other film makers would have been able to handle the situation properly, to break down the door and get in.