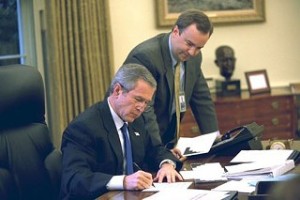

(In 2008, President George Bush’s press long-time press secretary Scott McClennan published his autobiography, What Happened: Inside the Bush White House. I talked with him in the middle of the press furor that it caused.)

A third-generation child of a family always in the public spotlight. A frat boy who went into the family business of living on the campaign trail. A veteran of Texas bipartisan politics who traveled from the Governor’s Mansion to the White House, a journey few early observers expected to see.

The similarities between George W. Bush and Scott McClellan, who served as Bush’s spokesman when he was governor, candidate, and president, are sometimes greater than the differences. But now the schism between the two over his memoir, What Happened: Inside the Bush White House and Washington’s Culture of Deception, has put the Austin-born and -raised McClellan at the heart of the debate about the current and future presidencies.

But when McClellan called from Washington, D.C., his first thought was about someone else from his White House years. “I don’t know if you’ve just heard about Tim Russert,” he asked. The NBC News Washington Bureau chief’s death had been announced only hours earlier. “Reality sinks in when something like that happens.” Of course, McClellan is back in the public arena because of the self-contemplation in his new book, which he will be discussing at BookPeople this Saturday. “I was born in politics. Most people choose it, but I was born into it,” he recalled. “I dedicated this book to those who serve, and none more so than those who want to get involved in politics. They will be able to learn some lessons from my painful experiences.”

McClellan’s description of his time in the White House centers on three key events leading to his exit: the Iraq war, Hurricane Katrina, and the Valerie Plame episode (aka “Plamegate”). He calls the invasion of Iraq a mistake, and “one of the most damaging aspects of embracing a permanent campaign mentality.” For McClellan, the war exemplified a compartmentalized, secretive White House that deceived itself and then the world. Bush’s advisers looked only for justifications for war, and then sold them like election promises. In that policy, McClellan said, “A fundamental mistake was that we didn’t approach it with openness and forthrightness when we went before the American people.”

Secondly, as McClellan sees it, the administration’s impotence and inaction in response to the devastation of the Gulf Coast sealed its political fate. “Until that point, a lot of Americans were starting to think, ‘We can’t trust this White House, because of what they said going into Iraq.’ And then Katrina comes along, and they start going, ‘Whoa, they can’t even handle this terrible natural disaster at home very well; no wonder they can’t get things under control in Iraq.’ So it became this issue of competence, in addition to the issue of trust.”

Finally, it was the administration’s deliberate leaking of the identity of active CIA agent Valerie Plame that was the greatest personal blow to McClellan – because the leak originated from people he knew and had trusted. “I became disillusioned when I found [Deputy Chief of Staff Karl Rove] had been involved and had misled me, and I found not too long after that that [Assistant to the President] Scooter Libby had as well. Now I didn’t know Scooter as well as I did Karl, but I still participated in meetings with them and sat across from them in senior staff [meetings].” It wasn’t simply that Rove lied to his face, but that Rove’s duplicity left McClellan feeding the same lie to those he saw as his ultimate employers: the American public. Then things got worse. “The big disillusioning moment, and there were a few in between, was nine months later when I found the president had secretly authorized disclosure of the National Intelligence Estimate. We had decried for years the selective leaking of intelligence information, and here I found out he had actually done that.”

So why a book, and why now? Though it might seem longer, it has only been a little more than two years since McClellan left the White House. McClellan recalls it was actually his predecessor as press secretary, Ari Fleischer, who suggested he write a memoir. (Fleischer, who wrote his own book, Taking Heat, told National Public Radio he was “heartbroken” by McClellan’s.) But his first step was to take some time off. “When you’re there as spokesman, you’re there to advocate for and defend the president’s policies and decisions; you’re not speaking for yourself,” he said. “I’d worked for the president for about 7½ years and the White House nearly 5½, and I needed time to decompress, get away from it all, and clear my head.”

McClellan began writing in July 2007, and says he delayed the book’s release “because I wanted to make sure I got my perspective right.” Amid accusations it was influenced by his editors or, as Rove charged, reads like the work of “a left-wing blogger,” McClellan has one strong defender for it being all his own work: his mother, Carole Keeton Strayhorn. “I know he wrote every word of that book because he has been e-mailing it to me for months and months in bits,” she said. “I would put in commas or periods or correct a typo, and he’d say, ‘You know, Mom, I do have an editor.'” So how does the former state comptroller to then-Gov. Bush feel about her son’s revelations? “I could not be prouder of Scott. I’m always proud of all my four sons, but I’ve never been prouder than now.” It’s not the runaway success of the book, she says: After all, in a family of high-achievers, Scott has already set a heady standard by becoming White House press secretary. Instead, she refers to what she told Scott’s brother, Mark. “I said, ‘I don’t know if he’ll sell a single copy, and I don’t care if he sells a handful.’ I said, ‘It’s good for him, because he knows who he is.'”

It’s not simply a personal autobiography or an attack on the Washington way of doing things, and it’s definitely not a shocking exposé of hidden Bush secrets. It is, McClellan hopes, an insider’s view of how Bush’s White House team played the Washington game harder, meaner, and more destructively than any previous administration. “When I was initially looking at responsibility, I was looking everywhere else; but responsibility lies first and foremost with the president. No one has a greater bully pulpit and platform from which to make the kind of change that is needed in Washington.”

He hopes the book becomes a lesson, for any future administration, of never taking power for granted, or never treating an election victory as carte blanche: That may be his greatest accusation against Bush, and his source of greatest disappointment. “One of the key things I wanted to focus on,” he said, “was how did this popular, bipartisan governor, at 70 percent-plus approval ratings for much of his tenure in Texas, become one of the most polarizing and unpopular presidents?”

Much of the criticism directed at McClellan is simple: once a Bush man, always a Bush man. But any close observer of Texas politics remembers that the partisan Bush presidency grew out of a bipartisan Bush governorship. Republican Bush often worked in close concert with the state’s two ranking Democrats: House Speaker Pete Laney and Lt. Gov. Bob Bullock. That spirit of outreach was part of what attracted McClellan, a longtime Republican but a self-proclaimed centrist, to Bush. Bullock “used to say the campaigning stops, and now it’s time to do what’s right for Texas,” McClellan said, and he thought that the lieutenant governor’s influence had rubbed off on the governor.

Laney, now retired and growing cotton in West Texas, believes that state constitutional checks and balances kept Gov. Bush constrained. “The governor of Texas has three powers under the Constitution – the power to make appointments, the power to veto legislation, and the power to call a special session,” said Laney. “The House can bust his veto, the Senate can bust his confirmation, and if he calls a special session, we don’t have to show up. So a governor is pretty well forced to work with the leadership in the House and the Senate.”

For Laney, the first signs of a change in the Texas political culture came when Bush became governor. “If you go back and look,” he said, “you’ll see quite a few quotes about the change of power, that members had to build political capital. I’d never heard that in my 30-something years in the legislative process, that someone would have to build political capital by voting against their district.”

To U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett, D-Austin, who first went to Congress the same year that Bush picked up the keys to the Governor’s Mansion, “Genuine bipartisanship is when you give a little, you get a little. You work out a way where there can be a win-win, where differing viewpoints are reflected, and you go away a little happy and a little unhappy. The George Bush version of bipartisanship is Zell Miller. It’s the idea that you get one nominal Democrat to make it appear like you have a compromise solution.”

Gov. Bush was also bipartisan when he couldn’t get his own way. In 1999, he wanted to slash the proposed Children’s Health Insurance Program budget, removing 200,000 children from CHIP eligibility: He was defeated by House Democrats. When he finally signed the bill, he sold it on the campaign trail as a bipartisan victory. As Rep. Glen Maxey, D-Austin, told the Chronicle at the time, “It’s shameless to take credit for something he wasn’t supporting.”

So, does Laney regret being the man who, from the floor of the Texas House, introduced President-elect Bush as “a leader we can trust and respect”? “I was speaking for the moment, so I don’t want to look back,” he said. “I still had a legislative process, and he was fixing to be our president.”

As with the Bush foreign policy failures, McClellan blames the advisers for the tactics that promulgated partisanship, but he does place ultimate responsibility on the president. He sees the president’s competitive personality as a factor but sees a key lesson for the president in how George H.W. Bush won and lost the presidency. “His father ran a pretty bare-knuckle campaign because his advisers said he had to in order to win the presidency in ’88. When he came into office, he tried to go back to what his more natural self was, with a more civil discourse, but the bad blood carried over from that campaign. Of course, he was defeated for a second term, and I think the president [GWB] made a decision and said, ‘Look, my father didn’t play the game the way it’s played in Washington, and that’s the reason he lost. I’m going to play the game the way it is played.'”

This was the root of the Bush permanent campaign that Washington only propagated. A Bush governorship hemmed in by the Texas Constitution became a Bush presidency unleashed by the might granted the office by the U.S. Constitution, and McClellan was one of a long list of Bushies who rode the campaign bus to Washington. Texans like White House Counsel Harriet Miers, Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, Federal Emergency Management Agency Director Joe Allbaugh, presidential counselors Dan Bartlett and Karen Hughes, and honorary Texans like Chief of Staff Andrew Card, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, and Karl Rove. There they met determined Texas GOP water carriers like Sen. John Cornyn and House Majority Leader Tom DeLay – and planned for the eternal Republican majority, without ever leaving the campaign bubble.

Calling the homemade kitchen cabinet “well-intentioned,” McClellan argues they were too close to the president for too long. “He needed more diversity of views; he needed more change within the White House and in other key positions, rather than a solidifying of the views that marched too much in lockstep with his own thinking.” He accepts that, as a campaign pro turned presidential staffer, this was also his sin. “By the time I became press secretary, I’d already served 2½ years. I thought two years would probably be my max as press secretary, and I ended up closer to three,” he said. The second term, he argues, became even more closed off than the first, as familiar names floated between offices, and the opportunity for new blood and new thinking was lost. “It was almost a strengthening of this loyalty to the administration. Colin Powell left; Condi Rice was put at the State Department; Andy Card continued, even though he tried to talk the president into making some changes; and a lot of other positions – like he elevated Al Gonzales to the Justice Department. It was this mentality that it wasn’t change; it was reinforcing exactly what the president wanted from his team.”

McClellan is not the first of the Bush entourage to write a book about his split from the White House. Former Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill worked with reporter Ron Suskind on 2004’s The Price of Loyalty. In the same year, Richard Clarke, counterterrorism adviser to four presidents, was heavily critical of the administration in his memoir, Against All Enemies. Before either, there was John DiIulio, director of the White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives. In an open letter to Suskind in 2002, DiIulio called the Bush kitchen cabinet “tight-knit and ‘Texas'” and dedicated to the permanent campaign. DiIulio wrote, “In eight months, I heard many, many staff discussions, but not three meaningful, substantive policy discussions. There were no actual policy white papers on domestic issues.” McClellan confirms DiIulio’s portrayal of a secretive, compartmentalized White House dedicated to re-election and how it made his job impossible. He said, “Some of the more consequential decisions were being made in a very small group, maybe two or three people with the president. So I didn’t have a clear idea of some of the motivations behind some of those decisions, and I had to rely on what I was provided and what I was told.”

Other prominent members of the Bush kitchen cabinet have more quietly detached themselves from the administration. Former Bush campaign chief strategist Matthew Dowd, another Austinite, slowly drifted away because he was concerned about the presidential bubble. In 2007, he told The New York Timesthat he had almost written an op-ed called “Kerry Was Right” but had backed away from such open criticism.

But there were key differences between these two groups. Clarke, DiIulio, and O’Neill were, in DiIulio’s words about himself, “not at all a close ‘insider’ but … very much on the inside.” Dowd, by contrast, was part of the ingrown Texas crowd that traveled with Governor, not President, Bush. They represented those who had been personally loyal to Bush the man. This makes McClellan unique: the first major insider and Texas holdover who has broken so publicly, so extensively, and so analytically with the administration.

James Moore, co-author with Wayne Slater of two biographies of Karl Rove (Bush’s Brain and The Architect), is not surprised this landmark belongs to McClellan. He said, “The people that had gone up from Texas, and all the Bush family friends, if you’d have vetted them, the one most likely to write this kind of book would be Scotty.” In part, he theorizes, that comes down to his highly political, highly educated background, growing up on the campaign trail. “His family aren’t exactly slugs,” Moore said. After treating McClellan as an unquestioning mouthpiece, he argues, the Bushies have no one to blame but themselves. “Their misjudgment of Scott is iconic of their misjudgment of everything.”

The attacks upon McClellan were to be expected, ranging from personality smears via the White House to attacks from the left for not coming forward sooner. According to another Austinite, ex-Bush media consultant and Public Strategies honcho Mark McKinnon, it’s a simpler issue. “I think it’s a violation of the professional code of ethics, and I thought it was the case when George Stephanopoulos wrote his book about Clinton,” he said. “I just don’t think you should kiss and tell.”

Even muted critics like Dowd were pilloried from all sides. “Matthew says that the thing that stunned him was not that you would have this official response from the team and the allies, but that he was attacked from the other side as well,” said Slater, senior political writer for The Dallas Morning News and a longtime Bush watcher. Just as Dowd was savaged by reporter and former Clinton aide Sidney Blumenthal – for keeping “a strange kind of post-betrayal omertà” – McClellan has been attacked for doing too little, too late. “He’s a person with no country,” said Slater.

But while he agrees with some critics that McClellan may have been delinquent in waiting so long, Slater warns against being too harsh. “If we continue to pillory the people who hold up truth to power, especially if they were part of the inner circle, what’s the message to people in the future? It’s basically, keep your mouth shut.”

McClellan understands the charges from both sides: He let the media down then and the administration down now. “The White House press corps often had a hard time trying to get through a very thick and tall wall that this White House put up, sometimes a wall that I was on the other side of myself,” he said. As for his former colleagues, he sees them “as well-intentioned, but [they] refuse to look back and come to terms with the realities of the situation.” The first step, he argues, may be the hardest personally. “You’ve got to be able to separate your personal fondness for the president from his policies and governance and leadership.”

So what now for McClellan? First, there is his scheduled appearance before the House Judiciary Committee on June 20, then finishing his book tour. Still only 40, he has to make decisions about his career that, for the first time in almost two decades, does not involve campaigning or Bush. “I’m entering unknown territory here,” he said.

But his greater concern, he says, is his hope the book may play some small role in improving political life. “I’ve been surprised by how many people across the country are appreciating that larger message about moving beyond the partisan warfare, to restore bipartisanship and candor and civility to the process in Washington,” he said. “Some people say we can’t, but I’m optimistic that it’s a matter of time until we do.”

McClellan has some advice for any future press secretary. “First and foremost, they need to ask the question, ‘Will I be able to attend any meeting I choose to at any time I choose to attend?'” Without that access, the chief policy mouthpiece for the administration can never know who on his own team is lying to him, and to the American people. “That’s who you ultimately serve, and it’s important not to lose sight of that.”

Richard Whittaker: I imagine it’s been a bit crazed for the last week.

Scott McClellan: Yeah. I don’t know if you’ve just heard about Tim Russert. It’s awful news. Reality sinks in when something like that happens.

RW: Out of the three things, getting involved in politics in the first place, becoming the White House press secretary, and the reaction to the book, which is the most surprising to you?

SM: That’s a good question. There were certainly surprises as press secretary, but what surprised me most about the initial reaction was how vitriolic and personal some of it was. No one was refuting the larger themes and perspectives of the book, and at the beginning, those that were personally attacking me hadn’t even read the book to see what my motivations were. I think they’re pretty well-described in the book. But that’s one of the problems I talk about with Washington. Instead of reasoned and honest debate and discussions of the issues that matter, we get caught up in this mentality of politics as war. That’s a very destructive process in Washington and something I hope in some small way I’m helping move beyond.

RW: It’s a very readable book, and one of the things that is very clear even if you don’t say it explicitly, is that the job of the spokesman is a responsibility to Americans and people beyond the White House.

SM: As press secretary, that’s who you ultimately serve, and it’s important not to lose sight of that.

RW: How hard was that, and how often was that made harder by the process in the White House?

SM: You read the chapter where I write about becoming press secretary, and how I struggled with whether or not I should go through with it, and delayed the announcement for a few weeks because I knew coming in that the White House operated in a certain way, and that no one was looking to change the way the White House operated. We were moving into an election year, and this White House tends to want to share a limited amount of information with the public. In a lot of ways, it has been self-defeating: The lack of openness, the lack of transparency, and the lack of candor with the American people, which I talk about at length, is one of the key reasons why this president’s credibility is so low, and his popularity is so low today. I dedicated this book to those who serve, and none more so than those who want to get involved in politics and want to serve, so they will be able to learn some lessons from my painful experiences during that process. Washington is certainly a lot different than the Texas I left when the president was governor there.

RW: Most of your political career was as a campaign guy, not only on your mother’s campaigns but on [state Sen.] Tom Haywood’s campaign.

SM: I was chief of staff to him too. He was pretty much a fiscal conservative but more moderate on other issues. He was a close friend as well as someone I worked for.

RW: Friendship seems to be a part of your political history; you’re obviously on good terms with your mother.

SM: Most of the time we were, but we had those moments in those campaigns. But I could tell her things a little more directly than others.

RW: Talking about the White House: Pierre Salinger, JFK’s press secretary, always said that the only time he was kept out of a discussion was when the best thing for him was to not know, but the default was for him to be around. He also talked about the diversity of voices around Kennedy. You look at the Bush administration, there’s all these people that came up with him, like Dan Bartlett and Karl Rove, Mark McKinnon, and Matthew Dowd, and Karen Hughes.

SM: The people you mention, by and large, are well-intentioned, but these are a group that had been with him from the beginning, back to the Texas days. They were loyal to him, and he was loyal to these individuals too. Now there was some effort to bring in some non-Texans, if you will, from Andy Card to Condoleezza Rice, which you certainly needed on the foreign policy side, you needed some experience. But one big problem of the administration has been that there was not enough change going on earlier. You get into the Washington environment, particularly in the White House, and in this day and age it’s tough to serve for more than two years and be as effective as you’d want to be. By the time I became press secretary, I’d already served two and a half years as deputy. I thought two years would probably be my max as press secretary, and I ended up closer to three. I talk in the chapter about triumph and illusion about how, as we moved into the second term, it was almost a strengthening of this loyalty to the administration. Colin Powell left, Condi Rice was put at the State Department, Andy Card continued even though he tried to talk the [president] into making some changes. And a lot of other positions – like he elevated Al Gonzales to the Justice Department. It was this mentality that it wasn’t change, it was reinforcing exactly what the president wanted from his team. I think he needed more diversity of views, he needed more change within the White House and in other key positions, rather than a solidifying of the views that marched too much in lockstep with his own thinking.

RW: You talked about your difficulty of accepting the position, but did you ever think, if I make this transition from deputy to chief, I’m part of the same problem?

SM: Looking back with that experience behind me, I would have approached that differently. I talk about how I thought, well, I know that certain things aren’t going to change, but I’m going to try to change them maybe gradually, within the office of the press secretary and within the White House communications structure. But it never really ended up changing and I probably would have had a more frank discussion with the president about some of the expectations, and thought more carefully about issues such as making sure I had access to any meetings at any time that I wanted to attend. I think that’s first and foremost. This White House is excessively secretive and compartmentalized, meaning you might be in the meeting where there’s discussion of policy, and world leader meetings and cabinet meetings and congressional meetings, but some of the more consequential decisions were being made in a very small group, maybe two or three people with the president. So I didn’t have a clear idea of some of the motivations behind some of those decisions, and I had to rely on what I was provided and what I was told. There were a lot of people that were good about sharing information, and some that weren’t. That’s a tough spot for a spokesman to be in at any time, and it’s not helpful to the president.

RW: One of the standout moments in the book for that was when Karl Rove told you that he hadn’t leaked [the Valerie Plame information], and you said this was someone you trusted and a Texan, someone you had known for many years.

SM: I became disillusioned when I found he had been involved and had misled me, and I found out not too long after that that Scooter Libby had as well. Now I didn’t know Scooter as well as I did Karl, but I still participated in meetings with them and sat across from them in senior staff [meetings]. That was the first real disillusioning moment for me, and it really undermined my credibility with the press and public, although some of my staunchest defenders in that period were some of the White House reporters who knew me and viewed me as someone they could trust. At the same time, I couldn’t defend myself, because the White House Counsel’s office said we could not say anything about the matter. The big disillusioning moment – and there were a few in between – was nine months later, when I found the president had secretly authorized disclosure of the National Intelligence Estimate. We had decried for years the selective leaking of intelligence information, and here I found out he had actually done that, and the only people who knew about it were himself, the vice president, and Scooter Libby, who the vice president told about it. It was a period of growing disillusionment over those final ten months, even though I continue to like the president personally and there are attributes about him that are very positive that I talk about in the book. But, like many people who go into elected office, sometimes they get caught up in some of our very basic human flaws that take us down a road that veers things off course. That’s what happened with us.

RW: There’s this division between Governor Bush and President Bush, almost as if they’re two different people. Do you think that people look more kindly on Governor Bush than President Bush because of the environment in which they worked?

SM: I think that’s part of it. In Texas, you had a very powerful lieutenant governor in Bob Bullock when the president became governor, and he used to say the campaigning stops and now it’s time to do what’s right for Texas. The national campaigns became so bitter and so hardball with their tactics that they don’t end when the election is over and they carry on into governance, and that’s a problem here in Washington.

I think the president, to a great degree, was influenced by his father’s time in Washington. His father ran a pretty bare-knuckle campaign because his advisors said he had to in order to win the presidency in ’88. When he came into office, he tried to go back to what his more natural self was, with a more civil discourse, but the bad blood carried over from that campaign. Of course, he was defeated for a second term, and I think the president made a decision and said, “Look, my father didn’t play the game [the] way it’s played in Washington, and that’s the reason he lost. I’m going to play the game the way it is played. I’ll make an attempt to elevate the discourse, and change things,” but I think he knew how hard that was and instead too easily succumbed to playing the game as it was, and playing it better than anyone else. That competitive spirit came into that mix as well. You can look back and say it may have helped us in the short term to win re-election, but in the long term I think it really hurt his presidency.

There was some interview I saw, it might have been a London interview on his European trip, when he was taking about how he looked back and he said something about regretting not doing more to change the tone, I think it was interesting that he was talking about that. Because, when you come into the White House – it certainly preceded us, this partisan warfare, for at least a couple of decades. But you have this massive political operation that really started during the Nixon administration: the institutionalization of the political operation inside the White House. It’s grown since then, and you have to have that counterweight to that political influence, otherwise the deliberation and compromise that goes into getting things done in politics is going to fall by the wayside.

RW: When that campaign process of no-holds-barred, whatever it takes, burn your opponent to the ground takes hold, if the only thing you’re moving towards is the next fight, it seems strange that it happened in the last seven years, when governance was really needed.

SM: Particularly in a time of war, when there needs to be some sense of bipartisanship and when I was initially looking at responsibility for things, I was looking everywhere else: but responsibility lies first and foremost with the president. No one has a greater bully pulpit and platform from which to make the kind of change that is needed in Washington. I’m encouraged that both candidates both talk about this. McCain talks about ending the permanent campaign, and I don’t think you can end it, but I think you can minimize its excesses; and Obama, of course, has run on the theme of changing the way that Washington works and bringing us together. But it’s very difficult once you get in there. More than anything else, first you have to have a president that is committed to a high level of openness and candor, and number two, constantly working to make sure you’re reaching out, that you’re governing towards the center, that you’re building trust between yourself and leaders of the other party. It’s not an easy thing to do in this environment, but the president has the greatest responsibility to make that kind of change.

RW: You talk about breaking the bubble, and this question of bringing too many campaign people onto staff. And one of the cardinal examples is Karl Rove, who, when Bush got into the White House, it felt like an office was created to keep him around.

SM: A lot of people have said he should have been inside the White House or outside the White House. Either way, he would have wielded a lot of political influence. Carville certainly did in the Clinton administration, and any political advisers for any future president are going to wield a lot of influence, whether they’re inside the White House or not. But he was given more ability to influence things than probably any other political adviser in modern history, and given a huge operation beneath him.

RW: And as was noted during the last gubernatorial election down here, having Robert Black as Rick Perry’s campaign spokesman and as his official spokesman, you had to check the letterhead to see which Robert Black was calling you. It just seems to institutionalize that.

SM: Texas, traditionally, has been stronger about making sure you have that separation in terms of ethics laws, but in Washington it’s much less clear. You saw that during the 2004 re-election: I wasn’t one of them, but there were aides that also had RNC e-mail accounts and Blackberries. There’s no separation there; it all blurs together and government becomes an appendage of political campaigning, rather than the other way around.

RW: There have been people who have left the administration who have been very public about their criticisms, like Richard Clarke and John DiIulio, and there have been others, famously Matthew Dowd, who have walked away quietly. But you are the first one who was really deep in who wrote a book: so why the book, and why now?

SM: It certainly wasn’t an easy book to write, and some of the conclusions that I came to were different to what my initial views were at the beginning of the process; but bottom line is that I want to see Washington change so that it governs for the better, and so that we don’t repeat these kind of mistakes again in the future. Oftentimes, you see someone at the end of their career, when they’re retiring from their job in politics or public service, and they decide, OK, I’m going to write a book about my experiences and the lessons that can be learned from them. It wasn’t easy to do at this point in my life or career, but I thought it was critical to have someone who was in the inside and walked within the inner circles who would give people a candid view, at least from my perspective of what exactly happened and why it happened the way it did. I hope that it would encourage others to come forward and do the same, although I’m not sure that will happen. But we need this for posterity and history’s sake.

RW: So when did you decide to start writing?

SM: A little irony here, given that he’s one of my critics now, but my predecessor [Ari Fleischer], when I was leaving the White House, I talked to him, and he said that you ought to mention when you’re leaving the ideas you’re exploring and that you might write a book. At that point, I wasn’t sure, and when I left the White House I needed some time away from it all, that’s for sure. I’d worked for the president for about seven-and-a-half years, and the White House nearly five-and-a-half, and I needed time to decompress and get away from it all and clear my head. When you’re there as spokesman, you’re there to advocate for and defend the president’s policies and decision; you’re not speaking for yourself. Now is the time to finally speak for myself. It was late 2006 when I started getting more serious about writing a book, and one of the key things I wanted to focus on was how did this popular, bipartisan governor, at 70% plus approval ratings for much of his tenure in Texas, become one of the most polarizing and unpopular presidents. How did that happen? That was late 2006, early 2007, and I started meeting with some publishers. I didn’t start writing until probably July 2007. I had some ideas that I wanted to explore, but the writing didn’t begin in earnest until July 2007, and I told publishers, this will be a candid look at this administration. I want to share my experiences and what I lived and what I learned from it. So it was a process that I went through, and it was over the course of not quite a year, from early July ’07 to mid-April ’08, when I was finally comfortable with it. I actually delayed the deadlines a couple of times because I wanted to make sure I got my perspective right. Part of that was obviously shaped by my upbringing, and the kind of person I am, and my views, which tend to be in a more centrist political position.

RW: I was talking to Mark McKinnon, and he thought you’d broken a code of professional ethics by writing a book.

SM: Ari has written a book, Karen has written a book, but I said if I’m going to write a book, I’m going to be true to myself and history. What other reason is there to write a book? You want people to be able to learn something from it. People that make the comments like Mark did, I understand where they’re coming from and their affection for the president, but you’ve got to be able to separate your personal fondness for the president from his policies and governance and leadership. I don’t know if I could have said at the beginning I was going to completely do that, but I believe I accomplished that, so that I could look at his governance rather than his personal attributes that I might hold in higher regard. Ultimately, your duty is to the American people and the truth, and the values that I was raised upon that taught me the importance of speaking up. So in a way, it’s almost a return to my roots, as well as an extension of my time in public service as a way to give something back. I think people that read the book see where I’m coming from and appreciate the sincerity within the words that I write.

RW: You talk about your days as president of your fraternity, and the decision to quit. It very much seems that the things that hurt you personally the most are not the things you did, but the things you didn’t do, like your failure to stop the hazing process.

SM: I made the effort to do something against the desires of a lot of people in that system. I won’t say I lost friends, because you find out who your true friends are in times like that and times like this, but people who I may have thought were friends, I lost during that time period, and those that were my true friends stood with me as they are now. Even former colleagues now know and respect where I’m coming from, even if they don’t agree with some of the views I express. There’s a certain social conformity that comes into play, too.

RW: Talking about people getting along, you talk about Condoleezza Rice, who was brought in as a foreign policy expert, but you think that she should have been the person that said to the president, have you considered this?

SM: The president has to accept responsibility for the decisions, but his advisers could have served him better, particularly in the foreign policy realm.

RW: When she was hired, a lot of people said, she’s very well-qualified as a Russian expert, but is that really what was required at that precise moment?

SM: Particularly when we’re beyond the Cold War at that point.

RW: That seemed like another instance of looking around within the people that were already known. But back to the book: Were you surprised that it became such a firestorm?

SM: I didn’t expect it to take off quite like it did. I expected some of the reaction because I knew that some of my former colleagues and some still at the White House would not like the fact that I was talking so candidly about my experiences. But in a lot of ways we’ve moved beyond the initial reaction, where some people tried to turn the book into these gotcha points, which is a problem in Washington in itself, not focusing on honest and reasoned discussion of the issues that are in the book. But now people are starting to focus on that larger message, and I’ve been surprised by how many people across the country are appreciating that larger message about moving beyond the partisan warfare and to restore bipartisanship, and restore candor and civility to the process in Washington. Some people say we can’t, but I’m optimistic that it’s a matter of time until we do, and until we have the right person come along who’s fully committed to making sure that they’ll get us there.

RW: Lloyd Doggett said that the reason that bipartisanship works is that you give a little, you get a little, and everyone walks away a bit unhappy. But everyone concentrates on that little bit of unhappy, and not what they got.

SM: Politics is the art of compromise, as I learned at a very early age, and it’s about getting things done. You can’t do that if it’s all focused on power and influence and manipulating the media narrative to your side’s advantage. There’s obviously going to be a breakdown somewhere.

RW: You’ve been in politics since you were a child.

SM: I was born in politics. Most people chose it, but I was born into it. As you know, it goes back to my grandfather [Page Keeton] and his career in public service, and his dedication to UT law school and the values he instilled in us as well. He was a tremendously positive influence not only on many prominent lawyers around the country, but in the family more than anything. I was very close to both sets of grandparents, but mom’s parents were living in Austin so we were closer to them. He influenced my brothers and me in a very positive way.

RW: So what are you planning on doing next?

SM: Once the book tour slows down a little bit, I’ll start to look at what’s next for me and look at opportunities. I knew going in, there were friends of mine that thought that maybe it wasn’t the best thing to do to write a book. I knew it was going to close some doors to me, but I’d like to continue to do things that build on the message within the book. Exploring the realm of possibilities, the academic world, whether or not it’s directly involved in politics, or involved in a way that can help bring about changes that I’d like to see from the outside. I’m entering unknown territory here, but I’m glad I did it. There are things that needed to be said, and things that needed to come from someone on the inside.

RW: There have been two interviews that have brought you a lot of attention.

SM: Olbermann and O’Reilly. When [Olbermann] turned around, he said, who’s more surprised to be here, me or you, and I said, the White House. The O’Reilly interview, he expressed his appreciation for me coming on the show and looking him in the eye, because he essentially told me that he could see that I really believed what I was saying, whether or not he agreed with me. The Olbermann interview was 45 minutes, and took up all but the last segment of the show. I thought we covered some good ground. It’s been an interesting few weeks, to say the least.

RW: If you could talk to the next White House press secretary, and give them any piece of advice to start up the kind of open communications that you talk about, what would it be?

SM: First and foremost, they need to ask the question, “Will I be able to attend any meeting I choose to at any time I choose to attend?” If they get a no, or the president’s noncommittal on that, they’re going to have to think seriously about whether they have the kind of flexibility on that to do the job as effectively as they would want to. The logistical aspects, I could talk about that at some length, about the 24/7 news cycle that they’re going to be living in, day in, day out, the long hours and so forth. I expect that future press secretaries will take a look at this book and hopefully learn something from it. Whoever is the next press secretary, I would want to visit with them if they so choose as to hear my views on thing.

RW: How has the press you dealt with at the time responded?

SM: There were some that had not initially read the book, and if they read the book would understand what I was saying. There were a few White House reporters that I think took umbrage to that, but I wasn’t singling out White House reporters. I was saying it was the national press corps more generally that was the problem. In fact, the White House press corps often had a hard time trying to get through a very thick and tall wall that this White House put up – sometimes a wall that I was on the other side of myself. There were exceptions to the rule, like the Knight Ridder reporters, [Jonathan] Landay and [Warren] Strobel, who went out and looked at the necessity of war and the intelligence and questioned it, and wrote some pretty tough and eye-opening pieces. There were too many in the general press corps caught up in the general atmosphere of, is the president winning or losing in his march to war in terms of bringing the public along, instead of looking at, well, is this necessary? What are the realities on the ground, what are the truths on the ground, and what are the long-term consequences? Part of that is that, just like me and many other Americans, we were swept up in the post-9/11 environment, and there was great benefit of the doubt given to the administration. Dan Rather interviewed me recently at the 92nd Street Y in NY, and I remember we had a conversation in advance of the interview, and he said, a time like that, you give some trust to the administration and the intelligence they have. We now know that it was misplaced. One of the most damaging aspects of embracing this permanent campaign mentality is when that’s transferred over into the war-making process. I say that the decision to go into Iraq was a mistake and wasn’t necessary, but a more fundamental mistake on the surface was that we didn’t approach it with openness and forthrightness when we went before the American people.

RW: If you contrast the “We will be greeted as liberators” rhetoric …

SM: The vice president and, I think, Wolfowitz were saying that.

RW: … to what Churchill said about “blood, sweat, and tears.” When it doesn’t happen, not only is there disillusionment, to the pros and the analysts, it just looks somewhere between naive and fantastical.

SM: Now you can look back at it, outside of that post-9/11 environment, more people see it clearly.

RW: Especially with Iraq, which was a country that didn’t control its own airspace, which barely had the budget for the internal suppression that was so important for the government.

SM: The priority for them was to survive and stop the populace from uprising. The intelligence was wrong, but it was more than just an intelligence failure. It was the way we went about making the case to the American people.

RW: You talk in the book also about the failures after Hurricane Katrina.

SM: Up till that point, a lot of Americans were starting to think, “We can’t trust what this White House because of what they said going into Iraq.” And then Katrina comes along, and they start going “Whoa, they can’t even handle this terrible natural disaster at home very well, no wonder they can’t get things under control in Iraq.” So it became this issue of competence in addition to the issue of trust. It really was a key moment that led to the president’s drop in support and undermined his leadership.

RW: So how do you feel personally about that?

SM: These were hard realities to come to terms with, and former colleagues I worked alongside and people I think are well-intentioned but refuse to look back and come to terms with the realities of the situation. I think that’s really unfortunate. The whole time at the White House and reflecting back on it was a political education I could never have imagined, and there were certainly things that I would do differently in hindsight.

(a version of this article previously ran in the Austin Chronicle)